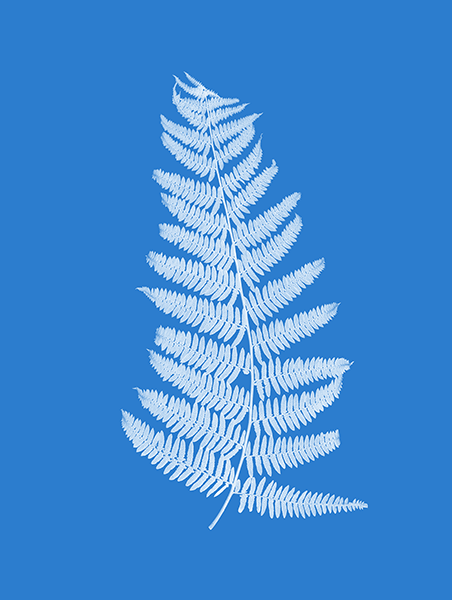

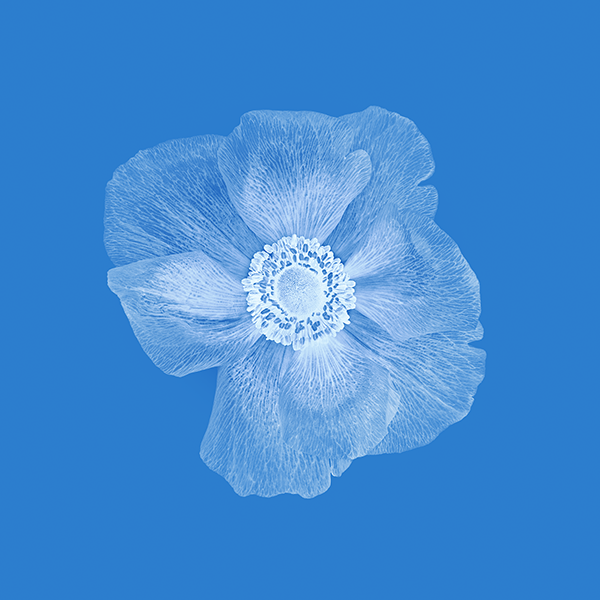

Cyan Ferns & Blue Dahlias

Please contact the gallery for the full list of works, pricing, and availability

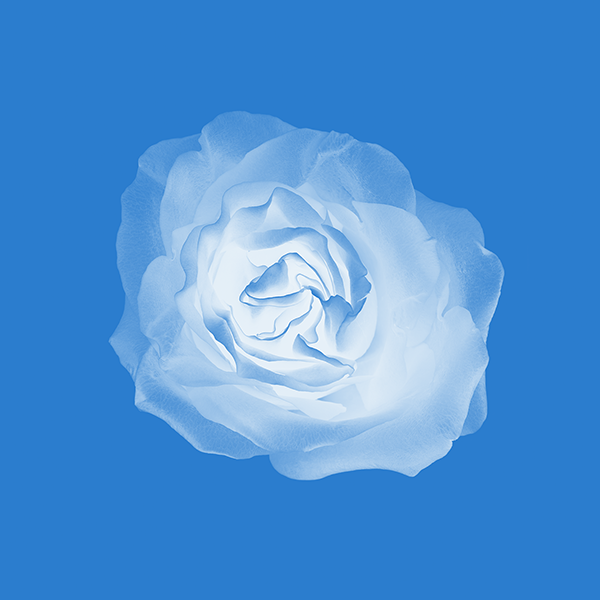

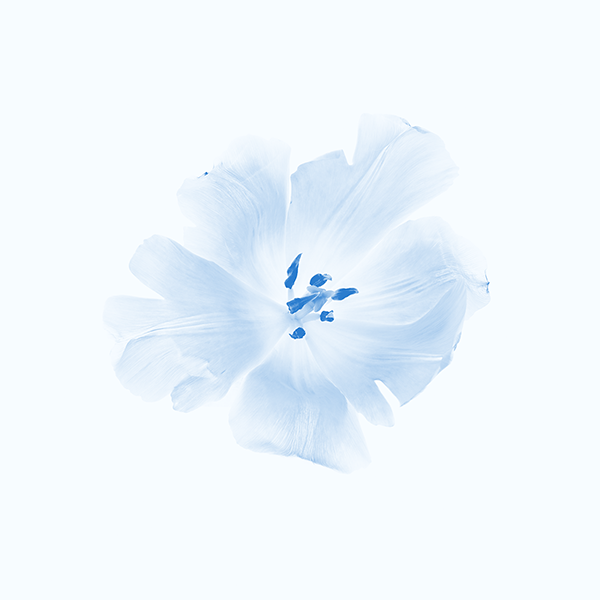

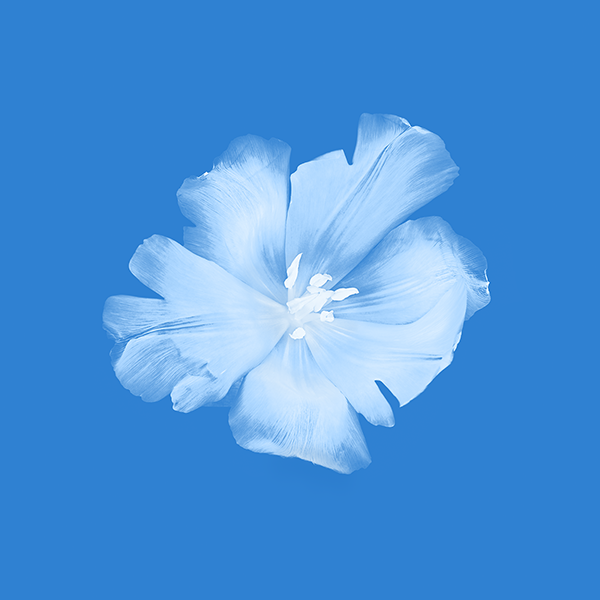

With Atkins’ herbals before us, we now face a typical, and very interesting, question from the years of early photography: how does the advent of a new technology graft itself onto a figurative tradition built up over centuries? The most illuminating instance, first emphasized by Gisèle Freund in the 1930s, is the continuity that linked the miniature (a small-format painted portrait) and the carte de visite (a small-format photographic portrait). In this case, the continuity is a truly striking one: the advent of new technology (photography on albumen paper) made accessible to a much wider and less aºuent public a practice – that of the small-format portrait – until then limited to the wealthier classes and aristocrats. However, in other cases, this new technological availability did not have equally linear consequences. […] The disclosure of the first photographic processes, such as Talbot’s photogenic drawing and Herschel’s cyanotype, o¤ered new horizons for the old herbarium tradition. But the new technology, as we have said, did not allow for results that might provide valid contributions to scientific research. A new genre was born – a distinct genre with independent functions and language.