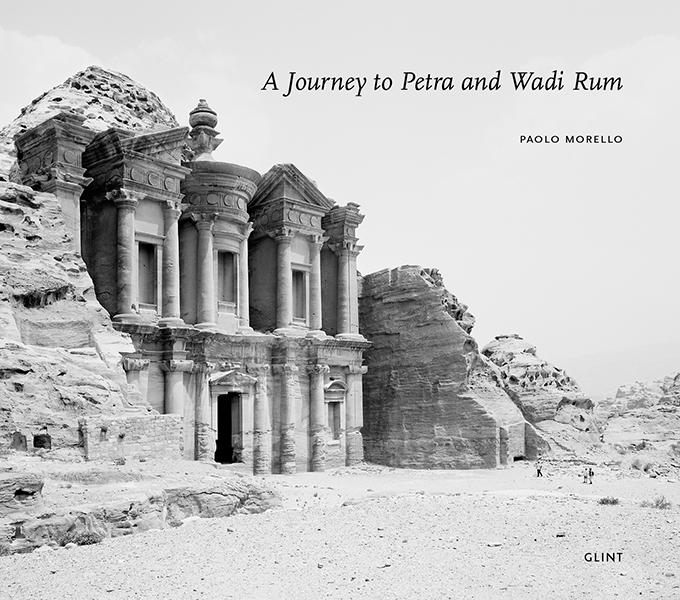

A Journey to Petra and Wadi Rum

Please contact the gallery for the full list of works, pricing, and availability

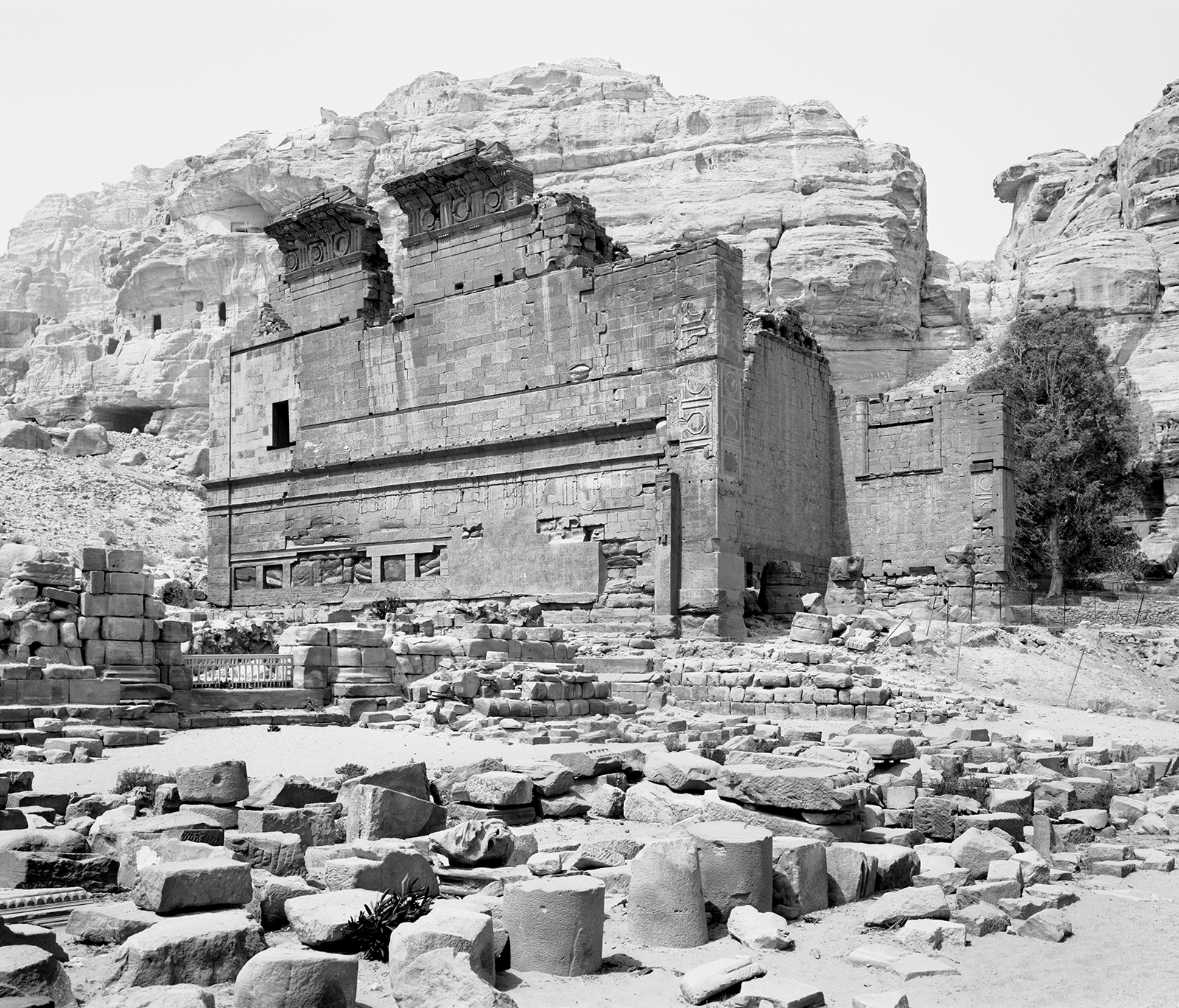

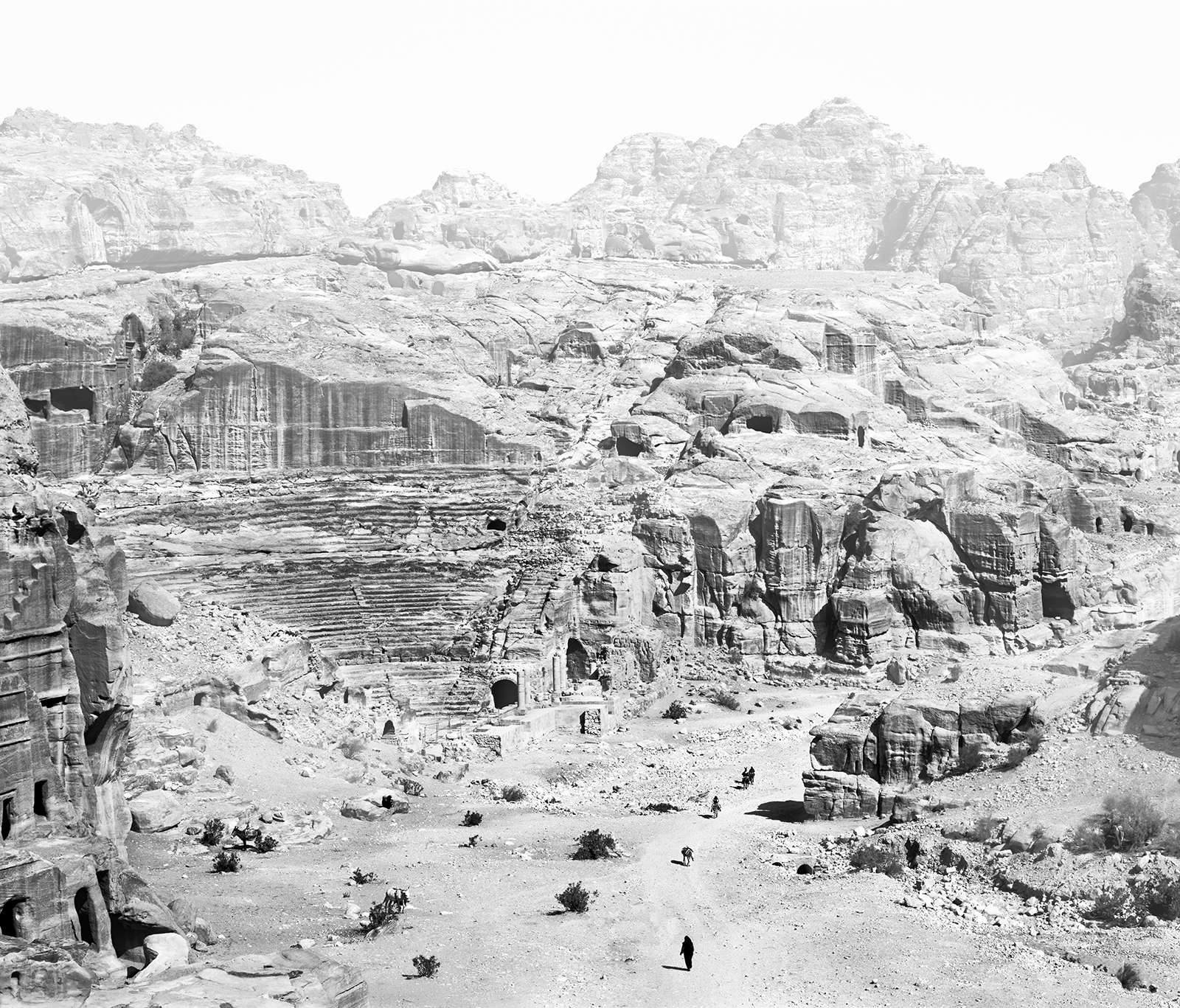

The oldest settlements in the area of Petra were inhabited by the Edomites – who were mentioned in the Book of Exodus – between the end of the VIII century and the beginning of the VII century BC. The town flourished a little later on thanks to the Nabataeans, an Arab nomadic tribe. In the first half of the II century BC the Nabataeans gave life to their kingdom, establishing in Petra their capital. Its ascent was mainly due to three different factors: the orography, which made it unconquerable, the abundance of water, and, most of all, the location. For several centuries Petra was the crossroads of the caravan routes from Aqaba and Yemen to Damascus and to Constantinople, which is to say, to all of the trade routes leading to a variety of goods – spices, incense, perfumes, and tar – from India to the Mediterranean countries and from Egypt to Persia.

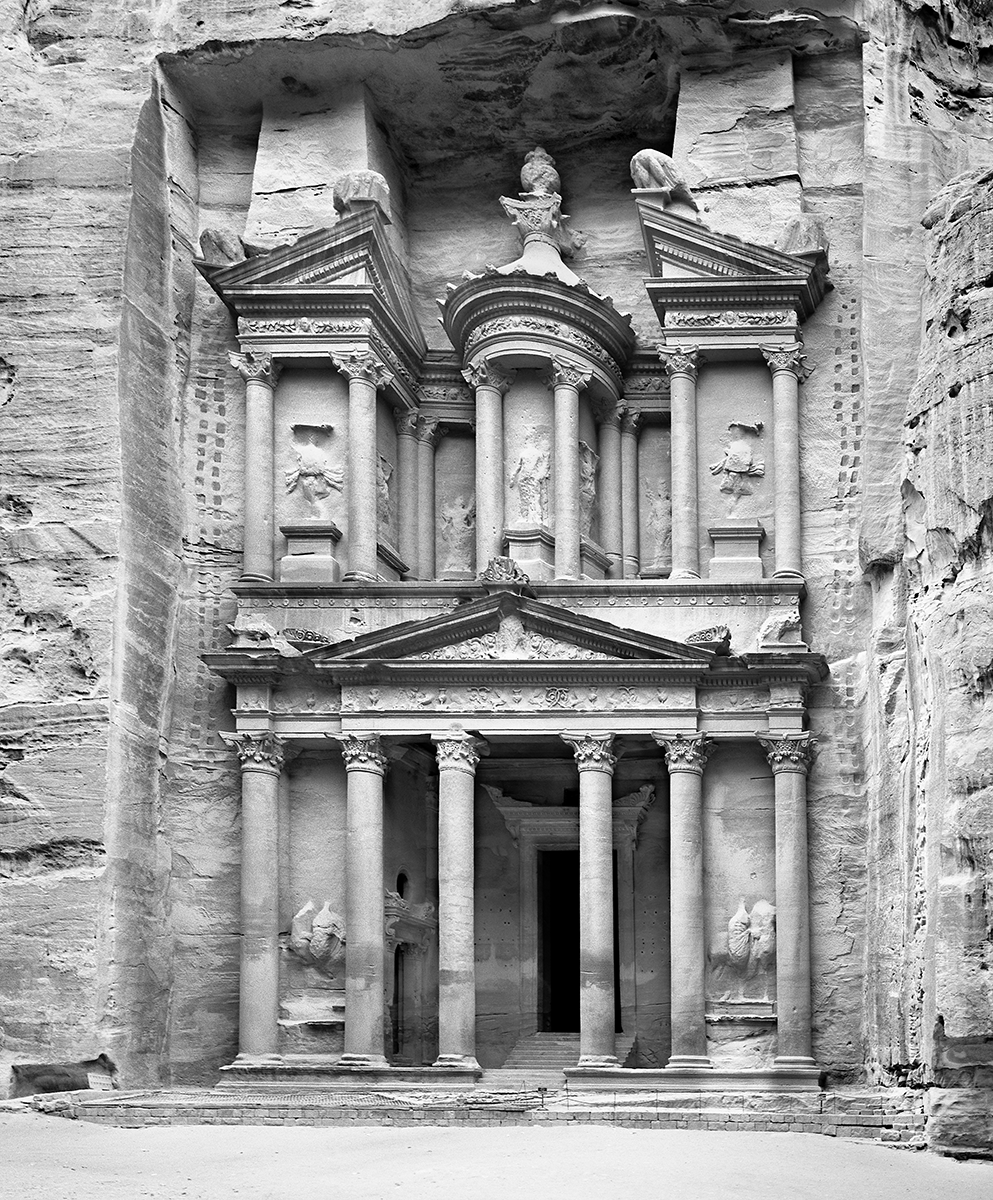

The first king of the Nabataeans of whom we have recorded evidence was ‘Ubayda I (known also as Obodas I), who ruled from 96 BC to 85 BC. After his death, he was worshiped as a god, and the most sumptuous grave in Petra was very likely dedicated to him, the so called al-Deir (the Monastery). Around 80 BC, the Nabataeans conquered the Seleucid territories, extending their domain northward as far as the Euphrates river and Palmyra. The son of ‘Ubayda I, al-Harith III (Areta III), expanded their kingdom further, all the way to Damascus. The other famous grave in Petra, al-Khazneh (the Treasury), which owes its name to the mistaken belief that the treasure of an Egyptian Pharaoh was hidden in it, is most likely dedicated to al-Harith III. Al-Harith’s greatest success was the agreement he negotiated with the Romans: by paying a huge toll in silver, the Nabataean kingdom ensured its substantial independence. Petra grew in power and wealth from 9 BC to 40 AD under king al-Harith IV, when its population reached about 30,000 people. Toward the end of the I century AD, the Romans shifted their trade routes to Egypt and along the Nile river; new towns became pivotal along the caravan routes, such as Bosra and Palmyra in Syria. In 106 AD the Nabataean kingdom was peacefully taken over by Rome. Bosra became the new capital of the Roman province called Arabia Petræa and from then on, Petra’s slow decline began.

After many centuries of oblivion, Petra was rediscovered in 1812 thanks to the Swiss explorer, Johann Ludwig Burckhardt. Born in Lausanne in 1784, forced to leave Switzerland to go to Germany and then to Great Britain, in 1809 he was employed by the African Association as a member of an expedition whose objective was to discover the source of the Niger river. For this reason, he spent time in Cambridge, studying medicine, surgery, chemistry, astronomy, mineralogy, Arabic, and training himself to endure long walks and rigid fasts. In order to improve his knowledge of Arabic language and culture he was sent to the Middle East. In Aleppo, in Syria, where he settled, he changed his identity, took the name of Sheikh Ibrahim ibn Abdallah, and learnt to dress like a native, pretending to be an Hindustan merchant. His knowledge of the Arabic language was so fluent that he was able to translate Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe. During his stay in Syria, he explored the region and its archaeological sites thoroughly – going to Damascus, to Baghdad, but also to Palmyra, and to Ba’albek in Lebanon. He wrote detailed reports in his daybooks about these travels, which were often very adventurous, and they were published after his death. He also reported about them in the letters he sent regularly to the African Association in London. In the summer of 1812 Burckhardt decided to go to Cairo along the Kings’ Road as far as Aqaba, heading to Timbuktu and to the source of the Niger river. With an excuse he convinced his guide to take him to Wadi Musa, a valley that the Bedouins guarded jealously as a secret. «It appears very probable that the ruins in Wadi Musa are those of the ancient Petra – he wrote in his journal – […]. At least I am persuaded, from all the information I procured, that there is no other ruin between the extremties of the Red Sea and the Dead Sea of sufficient importance to answer to that city. Whether or not I have discovered the remains of the Arabia Petræa, I leave to the decision of Greek scholars […]». (Johann Ludwig Burckhardt, Travels in Syria and the Holy Land. Description of a Journey from Damascus through the Mountains of Arabia Petræa and the Desert El Ty, to Cairo; in the Summer of 1812, London 1822).

Burckhardt was only twenty-eight when he rediscovered Petra. He died five years later, in 1817. The posthumous publication of his travel journals generated great interest and other travellers retraced his footsteps in the years to come. But at that time, Petra was extremely difficult to reach: the valley was off the ordinary routes taken by the archaeologists and artists who went to the Middle East and visitors were very likely to be robbed by the natives. It is therefore worth mentioning the journey of two young French men, Léon de Laborde and Louis Linant de Bellefonds, who reached Petra in 1828. They made a large number of sketches, which were widely circulated upon their return home, giving the Western public the first pictorial representations of the monuments of the Nabataean town. In particular, the book published by Léon de Laborde in 1836, Journey through Arabia Petræa to Mount Sinai, and the Excavated City of Petra, the Edom of the Prophecies, became a source of inspiration for David Roberts, a Sottish painter who in March 1839 travelled to Petra and to the Middle East with the precise purpose of painting a series of landscapes to sell on his return home. Thus Petra’s image began to take shape. Photographs, however, are much rarer evidence. One of the first known photographers was Louis Vignes, who arrived in Petra in 1864 with an expedition organized by the duke de Luynes, a collector, archaeologist and photographer himself, who between 1866 and 1874 would publish his account in a book illustrated with sixty-four photo-etchings and lithographs taken from photographs (Voyage of Exploration to the Dead Sea, and on the Left Bank of the Jordan, Paris 1874).

In 1985, Petra was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Since then, it has been the subject of an infinite quantity of pictures, which unfailingly represent always the same views, from the same perspective, without contributing much to a profound understanding of the place. Like many other touristic attractions, Petra today coincides with its image. The emotion of the exploration and the discovery, which one can feel pulsating in XIXth-century travellers’ journals, has vanished; it has been substituted, in the pictures taken by modern tourists, by an automatic process of confirmation of something already known, by the simple repetition of stereotyped images which have already been seen thousands of times. The photographs here on display strive to shatter these clichés. By avoiding the postcard effects of the ‘Rose-Red-City’ they hope to rebuild a dialogue with the XIXth-century travellers’ perspective, while illuminating the relationship between nature, rocks and architecture.